Introduction

Achalasia is surgically the most important and most common motility disorder of the esophagus. The name derives from the Greek a + chalasia = “failure to relax”.

The disease is characterized by a failure of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax and allow the peristaltic waves of the unconscious swallowing act to pass

‚CHALASIS - GREEK: "RELAXATION"

Pathophysiology & Pathogenesis

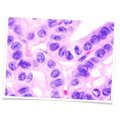

Pathophysiologically there is degeneration of the autonomic nerve plexus resulting in functional denervation of the esophageal musculature. Achalasia strikes 5-10 per 100.000 of population, usually striking those between 20 and 40 years old, which suggests an acquired disorder.

Exclusion of an underlying malignancy belongs to the differential diagnosis of dysphagia

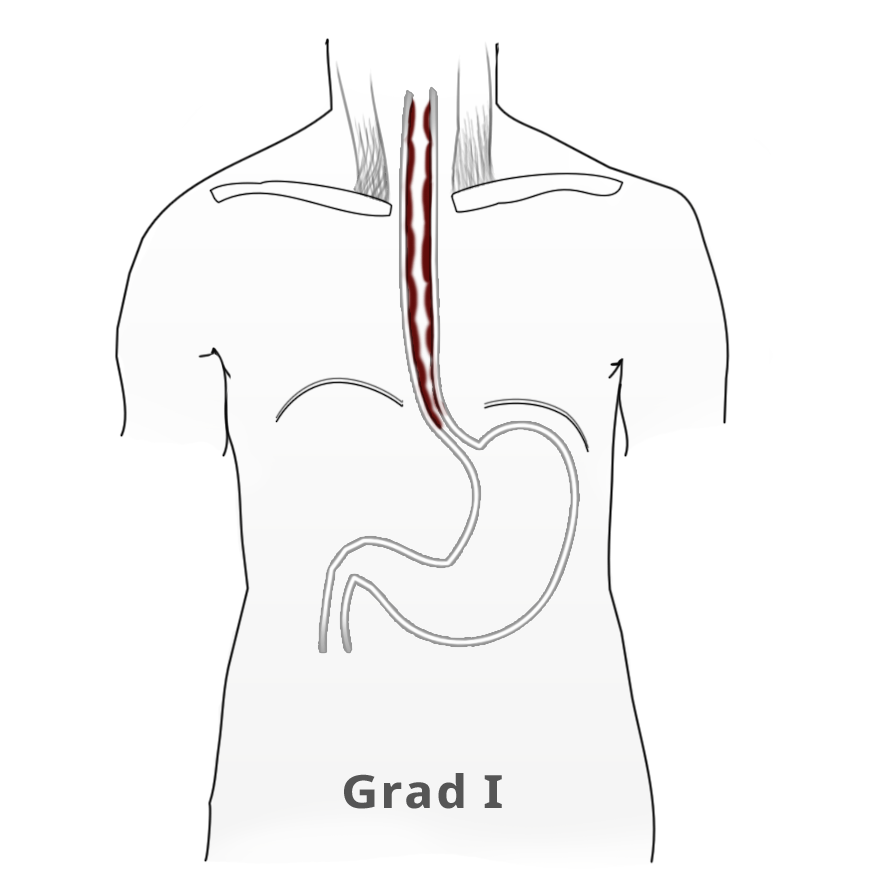

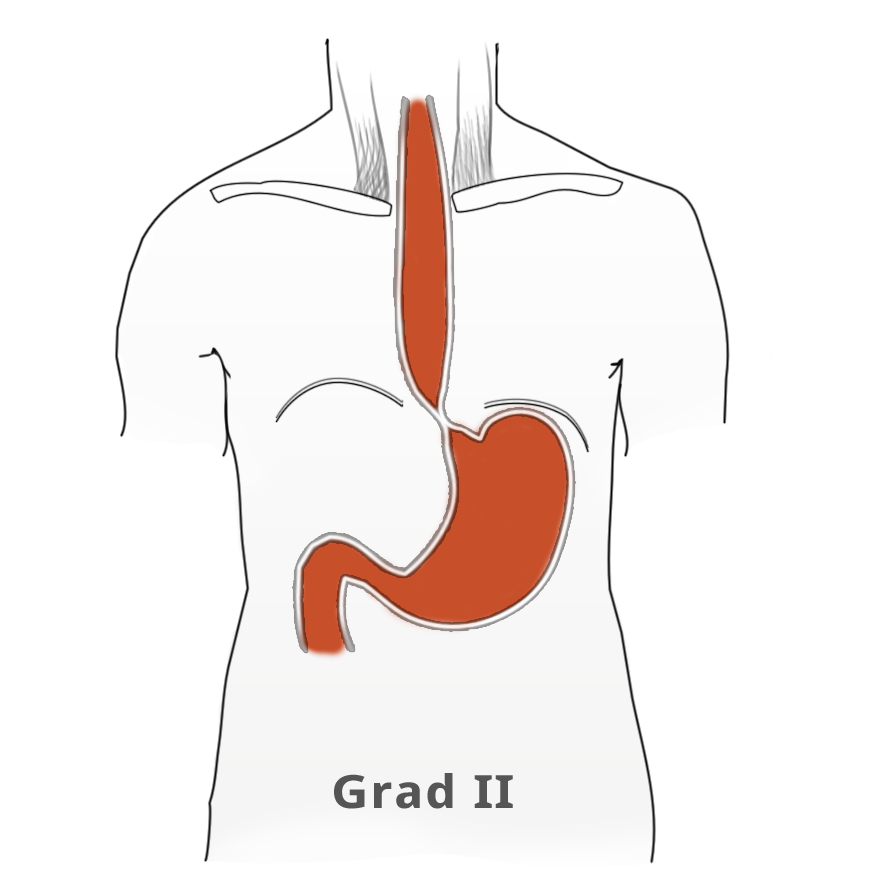

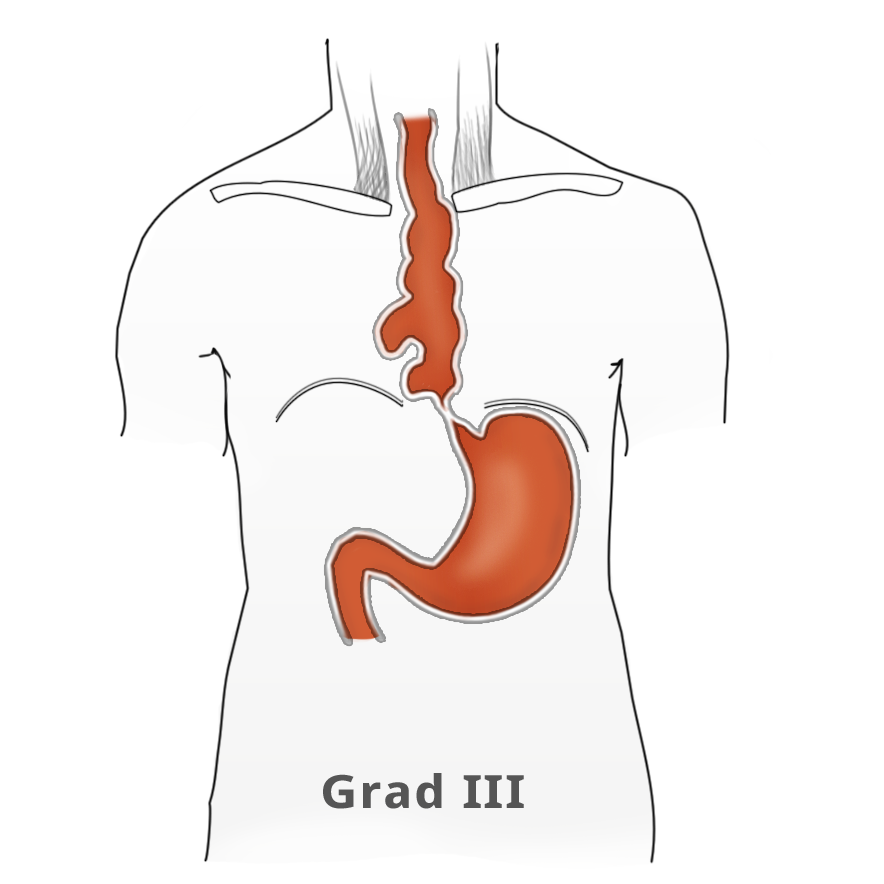

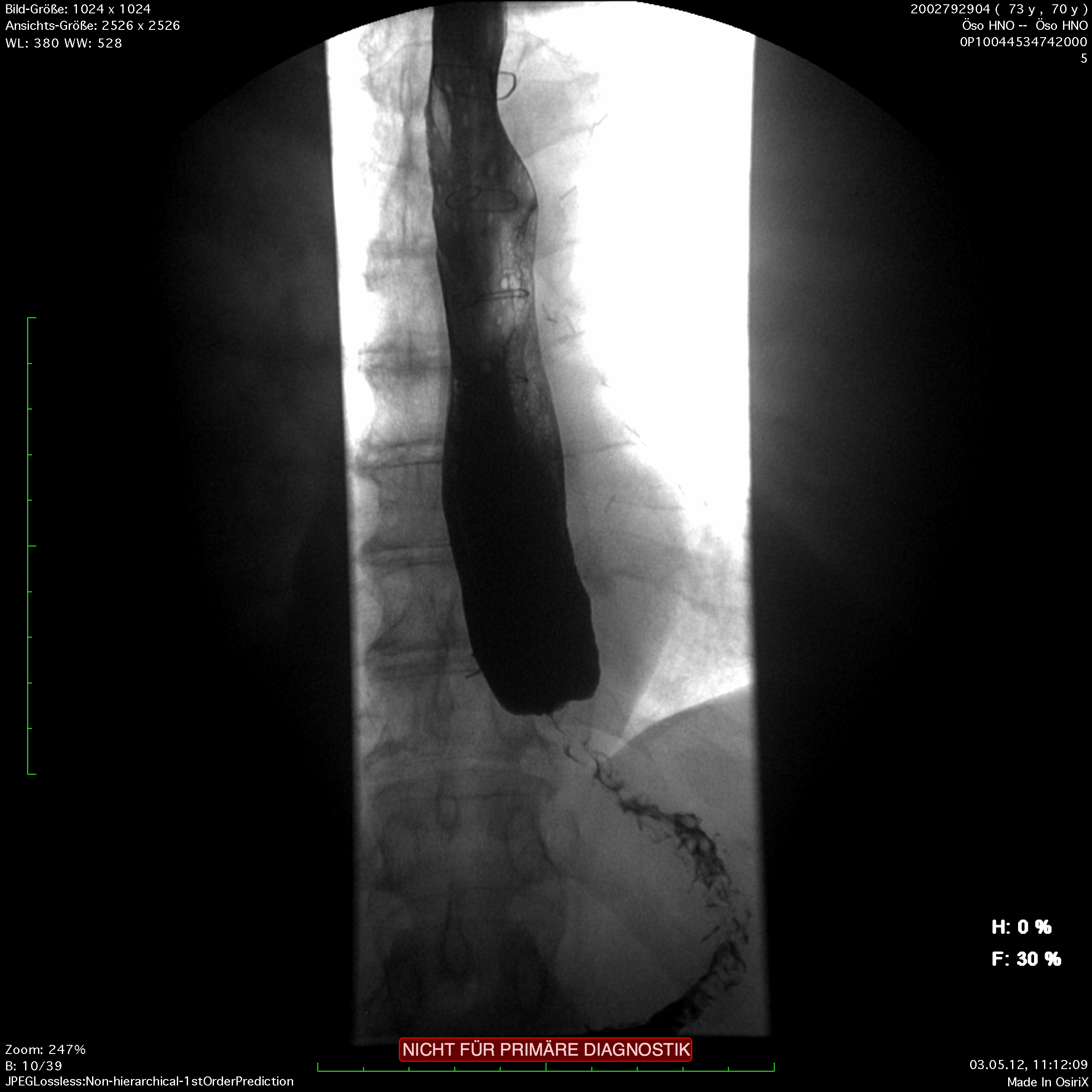

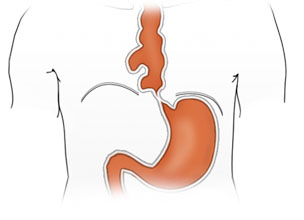

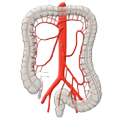

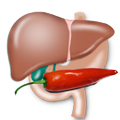

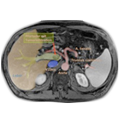

The elevated tonus of the lower esophageal sphincter and its incomplete relaxation lead to dilatation of the tubular esophagus. This gives achalasia its characteristic appearance in barium fluoroscopy. Primary idiopathic achalasia is distinguished from secondary forms, or pseudoachalasias, where e.g. a heart or esophageal carcinoma causes the dysphagia and morphological changes to the esophagus. Exclusion of an underlying malignancy belongs to the differential diagnosis of dysphagia and is done not only by the mandatory endoscopy but if needed by computed tomography (CT) as well.

Symptoms

Patients with achalasia report dysphagia, chiefly for liquid foods (paradoxal dysphagia), and regurgitation of undigested food. The patient’s report of non-acidic food intake can point to achalasia. Retrosternal pain associated with eating – but also independently of it – is an expression of disturbed motility and esophageal muscle spasm.

Untreated, achalasia progresses with increasing dilatation of the esophagus that can sometimes assume grotesque forms. There is also a risk of aspiration, stasis esophagitis, and -- in up to 20% of patients -- development of a secondary carcinoma.

Diagnosis

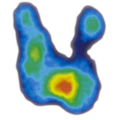

The classic image of a champagne glass or hourglass is seen in the fluoroscopic swallowing exam, an excellent tool for evaluating the extent of dilatation. An air-fluid level in the esophagus points to a stasis. Endoscopy can help to exclude secondary causes such as carcinoma. In addition, the stenosis stricture and surrounding mucosa can be evaluated and if necessary biopsied.

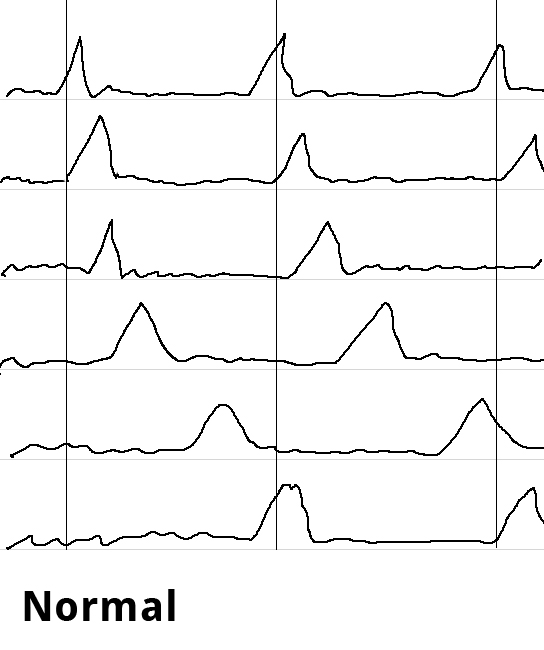

Endosonography can aid in the differential diagnostic clarification of a stenosis stricture. Definitive clarification, however, usually only succeeds after dilatation of the stenosis stricture. Esophageal manometry can show the disturbed motility as simultaneous contractions in the hypermotile form of achalasia while at the same time documenting the impaired relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter.

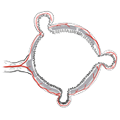

Swallowing is begun as a deliberate act and proceeds involuntarily as a peristaltic wave progressing aborally through the esophagus as the smooth muscle contracts sequentially downwards. Esophageal manometry is performed using a thin nasal probe with sensors to measure pressure at multiple locations along its length. The peristaltic waves produce staggered pressure waves in the captured images. Hypermotile achalasia exhibits tertiary contractions, the esophagus contracting simultaneously along its entire length. The simultaneous contractions can be readily imaged and constitute the classical manometric finding in achalasia.

Therapy

The goal of achalasia therapy is to lower the elevated tonus of the lower esophageal sphincter and eliminate the relaxation disorder responsible for the obstruction of the esophagus. Various treatment modalities are available. Drug therapy targets relaxation of the smooth muscles with agents like nitrates and calcium antagonists. But because success rates are rather poor, this option is little used. Interventionally, achalasia can be effectively treated by endoscopic Botox injection in the lower esophagus sphincter. The botulinum toxin blocks the motor end plates of the myenteric neurons, leading to improvement in symptoms in 60% to 80% of patients. The effect however is only temporary, so that renewed treatment is usually necessary.

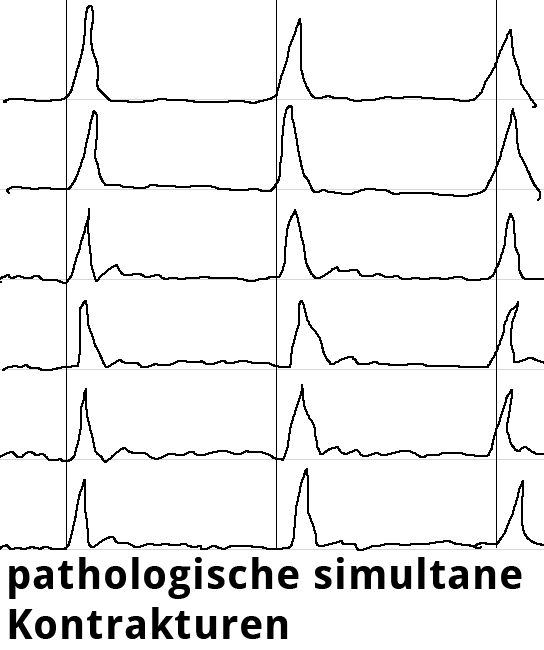

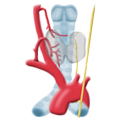

Another approach is pneumatic dilatation. Gastroscopy is used to insert a balloon catheter up to the gastroesophageal junction where radial pressure is applied to weaken the lower esophageal sphincter by tearing the esophageal muscle fibers. The risk of perforation is about 1% to 3%. A second dilatation is often necessary. This measure achieves improvement in 80% to 95% of patients.

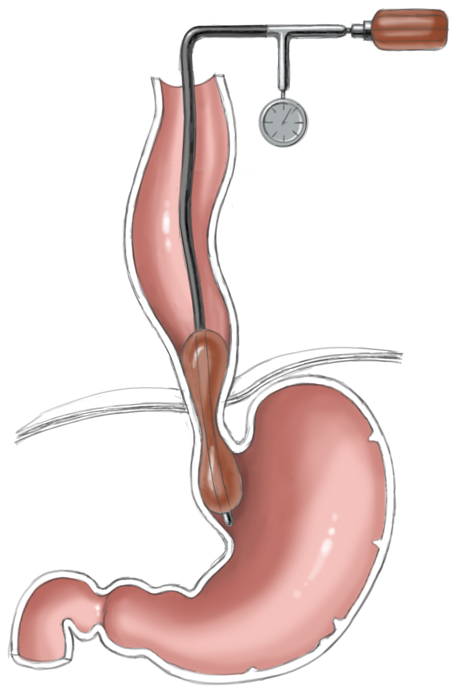

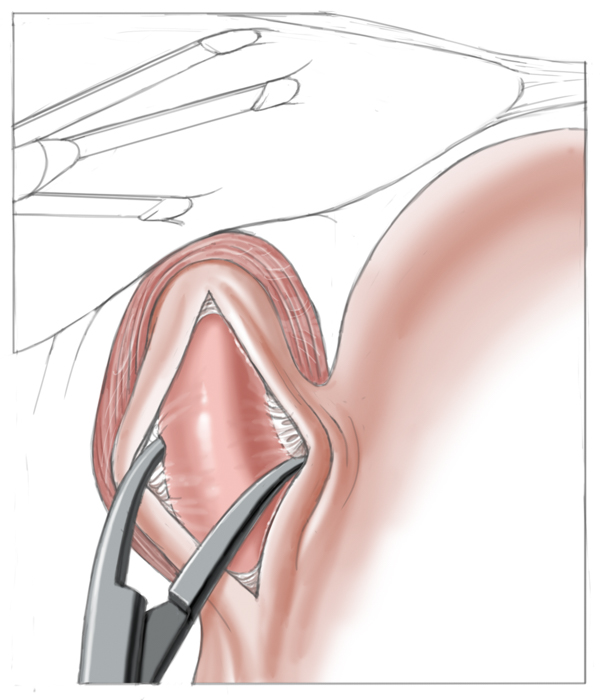

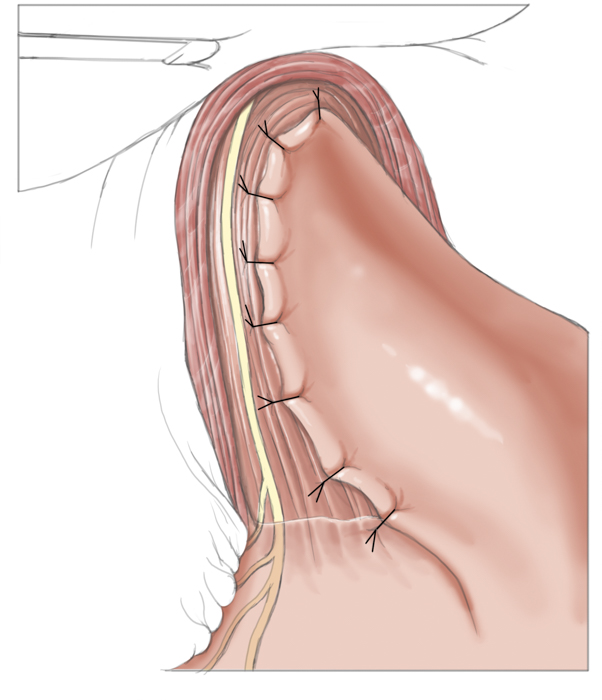

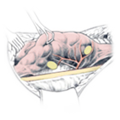

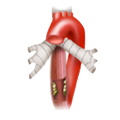

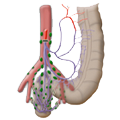

Operatively the muscles around the lower esophageal sphincter are split leaving only a narrow mucosal tube at the gastroesophageal junction. This of course entails a risk of perforation, especially after prior pneumatic dilatations, since tearing of the muscles can produce scarring and adhesions, which complicate layer-specific dissection.1 Destruction of the lower esophageal sphincter leads naturally to reflux of stomach acid into the esophagus. To prevent this and to cover the myotomy site, a fundoplasty is performed that covers the myotomy defect with a fundus sleeve. This procedure is called Heller myotomy combined with an anterior fundoplication according to Thal and Dor. Today it is usually performed laparoscopically and has a low morbidity rate.

Drugs

Relaxing agents

e.g. Nitrates & calcium antagonists

Endoscopy

Botox injection

Pneumatic dilatation

Operative Therapy

Laparoscopic Heller myotomy

Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM)

Therapeutic strategy

A 2009 meta-analysis encompassing a total of 7855 patients showed that combined laparoscopic myotomy and fundoplication is the most effective and safe method and thus the procedure of choice for treating achalasia. This combined procedure offers better control of symptoms than endoscopic procedures (90% vs. 68%), has a low complication rate (3.6%), and causes little postoperative reflux.2

A 2011 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine compared pneumatic dilatation with Heller myotomy and found the procedures had equal success and complication rates.3

The study however only covered results from a period of 1 to 2 years. Comparison of long-term results, of special importance for the mostly younger patients, cannot really be done. In the initial phase of the study, moreover, 31 patients who had suffered perforation of the esophagus during dilatation therapy were excluded, which naturally distorts the findings (Bild) in favor of dilatation. The presentation of other details favored dilatation as well, such as the duration of the surgical myotomy and handling of the intraoperative mucosa lesions, which were immediately treated and healed without complications but which the study equated with esophageal perforations resulting from dilatation therapy.

Whether one can speak of the two treatments as being of equal value is questionable. Which treatment is best for a given patient? Since young patients in particular often experience recurrence following pneumatic dilatation, surgical myotomy should probably be preferred.

Older patients and patients with an elevated risk profile should first undergo pneumatic dilatation and only after the 2nd or 3rd dilatation fails, undergo surgery. In high risk patients, botulinum toxin treatment can be used.

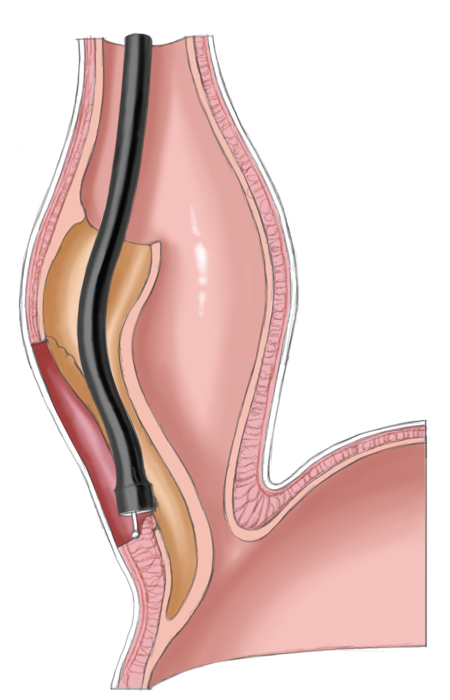

Peroral endoscopic myotomy

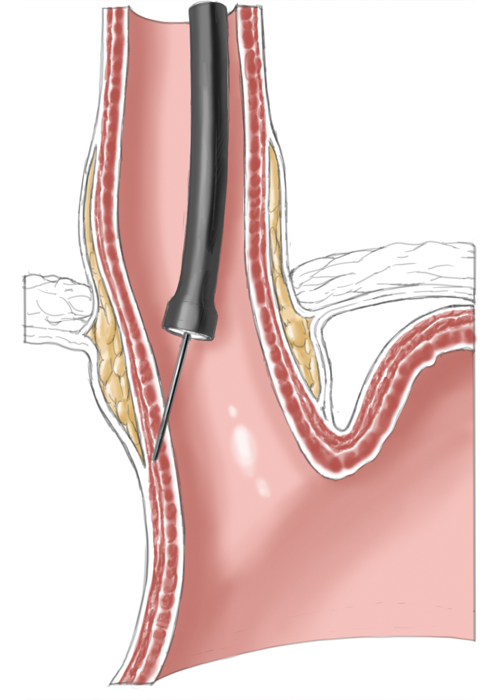

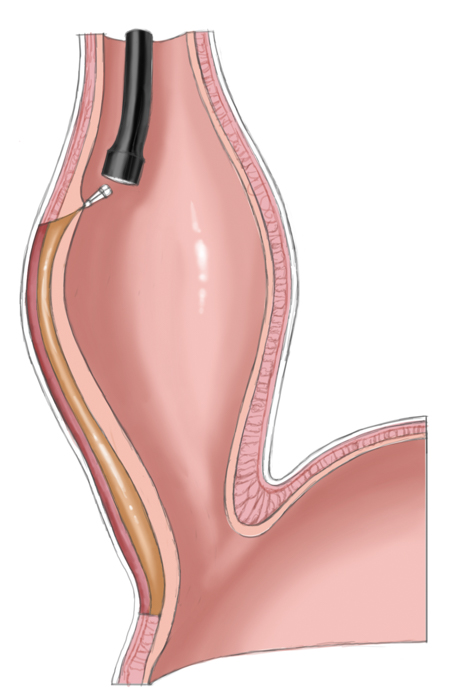

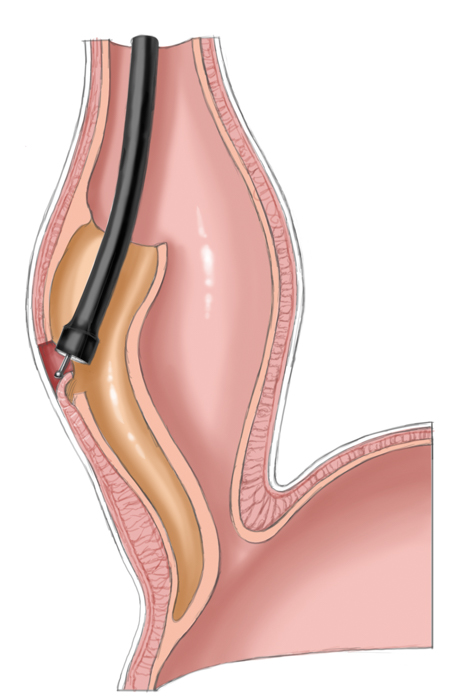

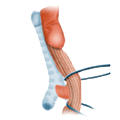

A relatively new procedure combines the advantages of interventional therapy with those of surgery. Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) employs a transoral endoscope to create a submucosal dissection tunnel. This is then used for endoscopic myotomy analogous to Heller myotomy, the sole difference being that the procedure is performed the side of the esophagus not intraabdominally. The mucosal defect is subsequently closed with endoscopic clips.

References

- Endoscopic therapy for achalasia before Heller myotomy results in worse outcomes than heller myotomy alone.Ann Surg. 2006 May;243(5):579-84; discussion 584-6.Smith CD, Stival A, Howell DL, Swafford V.

- Endoscopic and surgical treatments for achalasia: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Ann Surg. 2009 Jan;249(1):45-57.Campos GM, Vittinghoff E, Rabl C, Takata M, Gadenstätter M, Lin F, Ciovica R.

- Pneumatic Dilation versus Laparoscopic Heller’s Myotomy for Idiopathic AchalasiaJ Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011 Jul;17(3):324-6. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.3.324. Epub 2011 Jul 14.Wu JC1.

Wound Healing

Wound Healing Infection

Infection Acute Abdomen

Acute Abdomen Abdominal trauma

Abdominal trauma Ileus

Ileus Hernia

Hernia Benign Struma

Benign Struma Thyroid Carcinoma

Thyroid Carcinoma Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism Hyperthyreosis

Hyperthyreosis Adrenal Gland Tumors

Adrenal Gland Tumors Achalasia

Achalasia Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal Carcinoma Esophageal Diverticulum

Esophageal Diverticulum Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal Perforation Corrosive Esophagitis

Corrosive Esophagitis Gastric Carcinoma

Gastric Carcinoma Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic Ulcer Disease GERD

GERD Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric Surgery CIBD

CIBD Divertikulitis

Divertikulitis Colon Carcinoma

Colon Carcinoma Proktology

Proktology Rectal Carcinoma

Rectal Carcinoma Anatomy

Anatomy Ikterus

Ikterus Cholezystolithiais

Cholezystolithiais Benign Liver Lesions

Benign Liver Lesions Malignant Liver Leasions

Malignant Liver Leasions Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis Pancreatic carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma