Abdominal trauma

In about 20% of polytraumatized patients the abdomen is involved by blunt or penetrating trauma. In central Europe, blunt trauma at 95% far outnumbers penetrating injuries.

Blunt traumas are caused mainly by traffic accidents and falls from a height, penetrating injuries by stabbing, gunshot, explosions, and impalement.

Polytrauma

Polytrauma is defined as the simultaneous presence in one or more body regions of traumatic injuries, one or a combination of which is life threatening

Polytrauma Management

Abdominal traumas are associated with high morbidity and lethality since bleeding complications or secondary septic complications can occur after hollow organ injuries. The goal of every trauma management is to determine the extent and prognosis of the injuries. An adequate diagnostic workup must be completed in time and the priority of the treatment sequence determined.

Polytraumatized patients are usually treated in a so-called shock room, in which a trauma team representing diverse specialties can administer primary and acute care. The first hour following a severe injury is a critical period in which the patient must be stabilized. After this “golden hour of shock”, there is a statistically sharp rise in the complication rate and lethality.

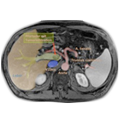

The further treatment in the shock room depends on whether the patient is hemodynamically stable or not. After the initial stabilization phase comes the diagnostic phase. If available whole body computed tomography is performed if indicated by the severity of the trauma. Alternatively, sonography of the abdomen can demonstrate large volumes of free abdominal fluid with high sensitivity. If free abdominal fluid is found and the patient is hemodynamic instable, immediate laparotomy must be performed.

Penetrating Abdominal Injuries

For gunshot wounds laparotomy is obligatory, it is imperative that all intra-abdominal accompanying injuries are conclusively clarified and treated. The exit wound is usually larger than the entrance wound. High-velocity bullets with high kinetic energy traumatize the tissue more than low velocity bullets. A bullet passing through the body creates a channel that is far larger than the caliber of the weapon used.

Caveat: From the location and size of the entrance wound conclusions can NEVER be made regarding the extent and localization of the intra-abdominal injuries!

Blunt Abdominal Injuries

In blunt abdominal trauma, the spleen is the most commonly injured parenchymatous organ, followed by the liver and intestinal hollow organs. In addition to intra-abdominal injuries, accompanying avulsion injuries due to shear forces or deceleration trauma can occur, chiefly affecting vessels and attached organs parts (partien).

In arriving at the diagnosis, attention should be paid to impact and seat belt abrasions. An unstable thorax or pelvis should always be understood as a sign of possible accompanying intra-abdominal injuries. Bleeding from body orifices, shock or local peritonism are further warning signs.

Rupture of the Spleen

Injuries to the spleen are clinically-radiologically divided into five grades. About 50% of spleen lesions are primarily to be treated surgically. If possible, an attempt is made to save the organ since asplenia can lead to complications, such as an increased risk of infection and the feared overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI) syndrome. After splenectomy, therefore, the patient must be immunized against pneumococci, hemophilus influenza, and meningococci.

Depending on the severity of the injury, several surgical procedures are available, ranging from parenchymal sutures to coagulation to partial or complete splenectomy. Conservative therapy is still reserved for hemodynamically stable patients with isolated splenic trauma. They require close clinical and radiological monitoring. There is a danger of two-stage splenic rupture with bleeding in the interval, the pressure from the hematoma leading directly to tearing of the splenic capsule or after minor trauma.

Liver Rupture

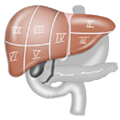

Injuries to the liver are divided into 6 grades of severity. In 50% of cases further abdominal injuries are present. The high lethality of liver rupture is due to these accompanying injuries and to bleeding complications.

Most liver ruptures can be treated conservatively (up to 85%). Laparotomy must be performed on all unstable patients. The type of surgery depends again on the severity of the rupture and ranges from parenchymal sutures to temporary packing of the liver with hemostatic dressings to resectional debridement.

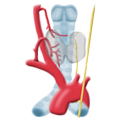

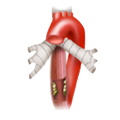

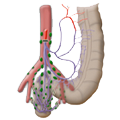

Bleeding can be controlled using the Pringle maneuver, in which the hepatoduodenal ligament is clamped, stopping blood flow through the portal vein and hepatic artery while omitting the common bile duct. This reduces the blood supply to the liver, allowing more time to treat the lesion.

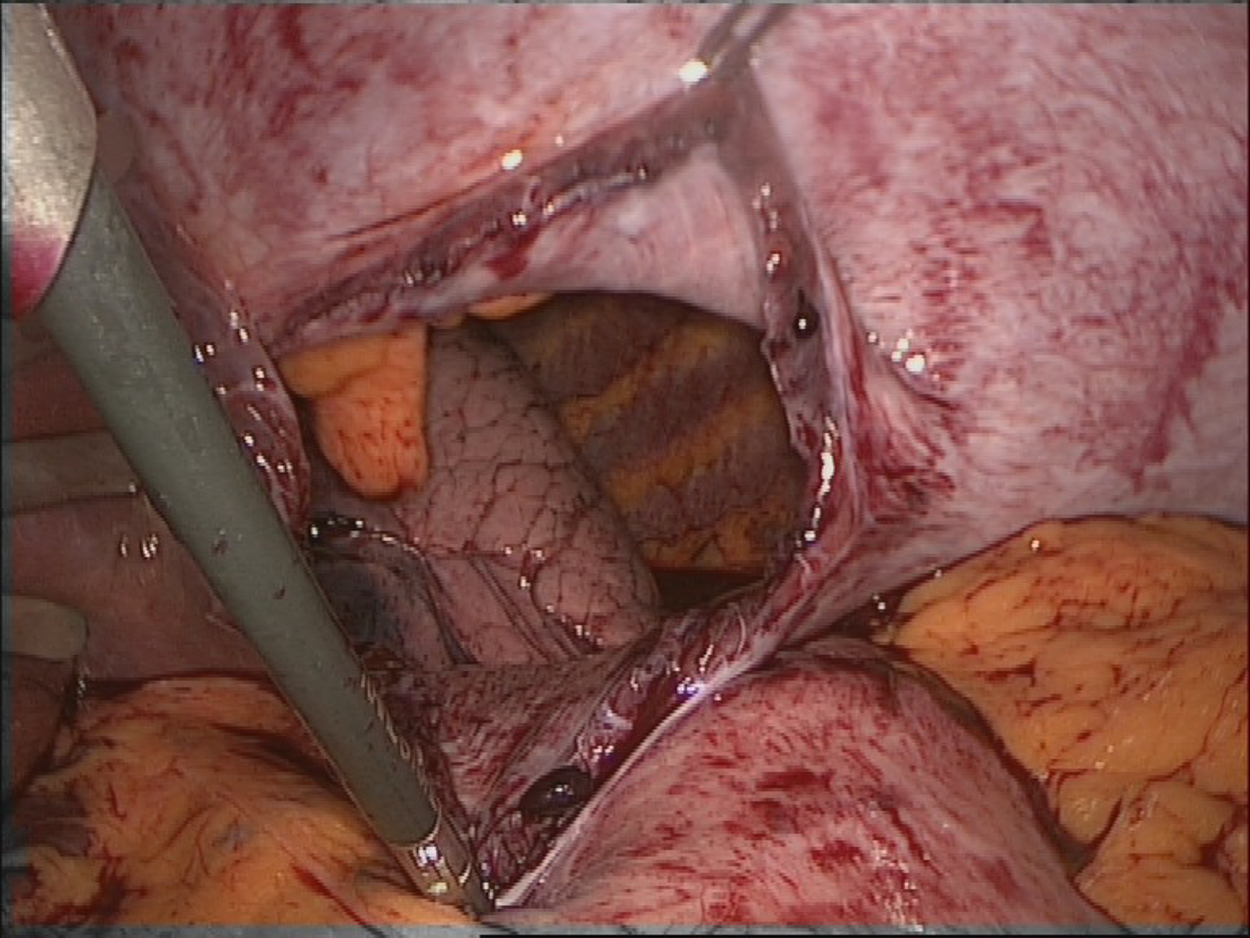

Diaphragm Rupture

Traumatic rupture of the diaphragm can be difficult to diagnose. Often it is overlooked in the initial diagnostic process. A sudden rise in intra-abdominal pressure can lead to diaphragmatic rupture, which occurs preferentially on the left side because the liver cushions peaks of pressure on the right. If laceration of the diaphragm occurs, intra-abdominal organs in the thorax may be displaced. If the injury is initially rather slight, an enterothorax may only form over the course of many years post-trauma.

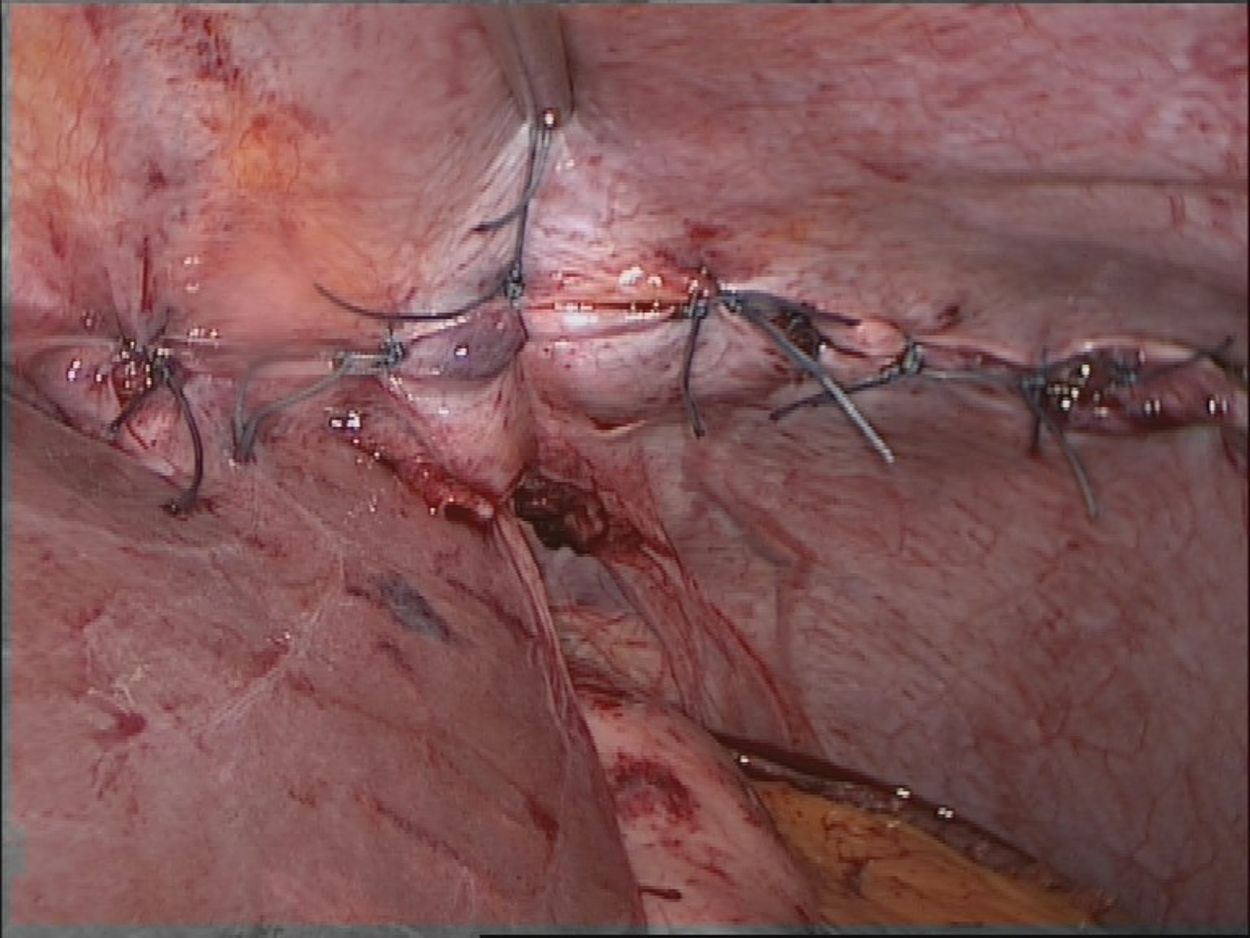

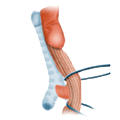

A rupture of the diaphragm is an unequivocal indication for surgery. The treatment of choice is suture of the diaphragm with non-resorbable suture. Depending on the location and extent of the rupture, this is done laparoscopically or openly, with transabdominal or thoracic access.

Wound Healing

Wound Healing Infection

Infection Acute Abdomen

Acute Abdomen Abdominal trauma

Abdominal trauma Ileus

Ileus Hernia

Hernia Benign Struma

Benign Struma Thyroid Carcinoma

Thyroid Carcinoma Hyperparathyroidism

Hyperparathyroidism Hyperthyreosis

Hyperthyreosis Adrenal Gland Tumors

Adrenal Gland Tumors Achalasia

Achalasia Esophageal Carcinoma

Esophageal Carcinoma Esophageal Diverticulum

Esophageal Diverticulum Esophageal Perforation

Esophageal Perforation Corrosive Esophagitis

Corrosive Esophagitis Gastric Carcinoma

Gastric Carcinoma Peptic Ulcer Disease

Peptic Ulcer Disease GERD

GERD Bariatric Surgery

Bariatric Surgery CIBD

CIBD Divertikulitis

Divertikulitis Colon Carcinoma

Colon Carcinoma Proktology

Proktology Rectal Carcinoma

Rectal Carcinoma Anatomy

Anatomy Ikterus

Ikterus Cholezystolithiais

Cholezystolithiais Benign Liver Lesions

Benign Liver Lesions Malignant Liver Leasions

Malignant Liver Leasions Pancreatitis

Pancreatitis Pancreatic carcinoma

Pancreatic carcinoma